Are veganism or offsetting effective asks for our movement?

And if not, what other calls to action could we be advocating for?

One of the most defining calls of the animal freedom movement in the past decade is the simple and direct: “Go vegan”. For some, perhaps even many in the movement, this call to action answered the burning question: “What can I do?” In the face of overwhelming exploitation and suffering, making an immediate change, however small, felt like a relief. This was something we could directly change, and for many of us, it felt more like empowerment than sacrifice. This was not a diet change – it was a boycott against violence. A refusal to be hoodwinked by industry lies. An act of solidarity with animals who did not consent to what was being done to them.

Those in the movement who are vegan are living proof that this call to action works, and that it can even lead people to dedicating their lives to this cause. But “Go vegan” has its limitations. It’s currently still a high-commitment ask. It can recruit deeply, but can it recruit broadly?

Recently, a growing debate within the movement has questioned whether encouraging diet change is the right primary ask, with some proposing financial 'offsetting' of animal harm as more effective. But is that really the better alternative? And what unhelpful narratives might it be reinforcing?

When can “Go vegan” backfire?

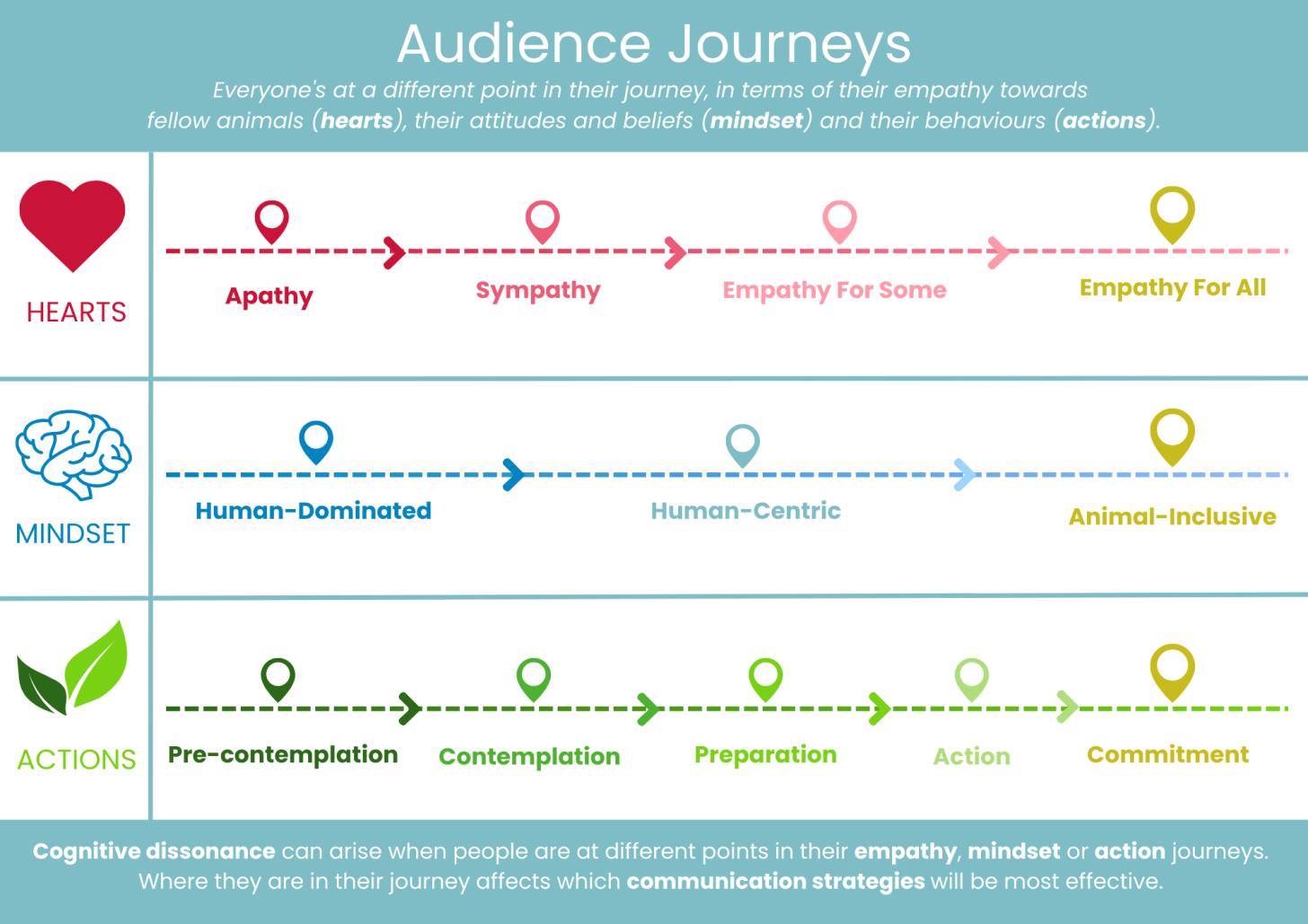

For people further ahead in their journey – already questioning society’s relationship with other animals and contemplating change – “Go vegan” is an invitation to align actions with values.

For people further back in their journey, the same message can land completely differently. It can often be heard as a demand to assume an identity they might not want, or a demand for a sudden leap they’re not yet ready to take. Instead of inviting people into our movement, it can feel like they are being called out on who they are and how they live their lives. This tends to trigger defensive psychological responses, as it’s perceived as threatening both:

personal autonomy

one's sense of being a good person.

The result? Misdirected hostility. ‘Militant vegans’ become the enemy, rather than the industrial system harming and killing animals. The people we most need to reach can disengage from the message and instead push back against its messengers – and our movement.

Has veganism reached its peak?

Various studies cite the number of vegans in the UK to be around 3–4.7%. While the number of people identifying as vegan has been increasing overall, its growth has slowed down in the last few years.

Some in the movement have responded by publicly critiquing individual change as ineffective, even declaring it a failed strategy. Others have doubled down, insisting that veganism is the only morally consistent ask and anything less is betrayal. Meanwhile, animals continue to suffer and be killed in numbers too vast to comprehend.

But what if the plateau is not a verdict on veganism, but an invitation to evolve our strategies and expand our asks?

What stage of veganism are we at?

Three complementary frameworks can help reveal veganism’s current position in UK society, and what might be needed next:

1

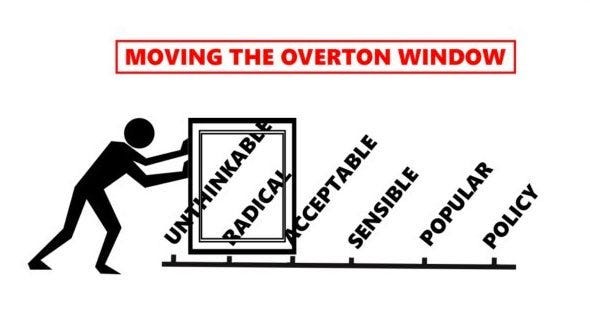

The Overton Window can show veganism’s journey through social acceptance: from unthinkable and radical through most of the 20th century, to increasingly acceptable in the 2010s and 2020s. Now, in 2026, veganism likely sits somewhere between acceptable and sensible, as recent research indicates that 71% of Brits see veg*nism as the most ethical diet.

2

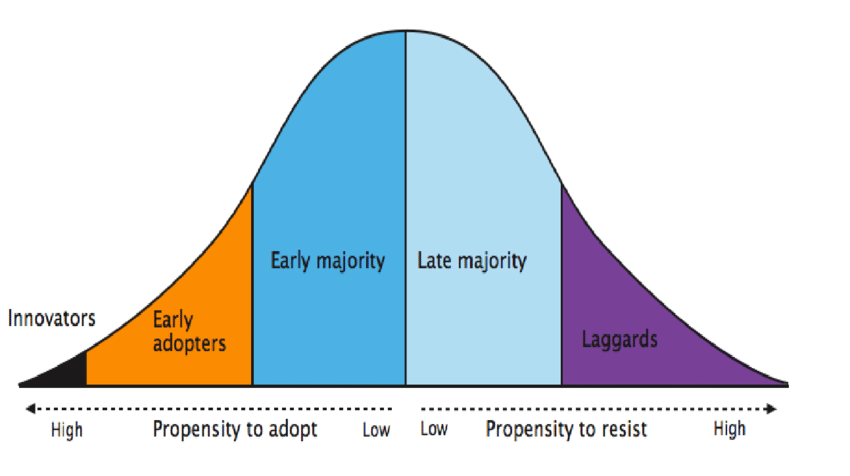

The Innovation Adoption Curve can help explain why vegan numbers currently hover around 3–4.7%. Developed by sociologist Everett Rogers, this model maps how new ideas and behaviours spread through society along a predictable bell curve:

Innovators (approx. 2.5% of a society) are the risk-takers who will adopt change regardless of social costs.

Early Adopters (13.5%) are more hesitant, but will still embrace change earlier than most and go on to influence others.

Early Majority (34%) adopt only after seeing it work for others.

Late Majority (34%) follow due to social pressure and normalisation.

Laggards (16%) change last, if at all, and often only when they have little choice.

Those who have gone vegan despite any social costs likely constitute most Innovators and some Early Adopters. Current vegan numbers do not necessarily represent failure; they could reflect what the adoption curve predicts at the slowest stage of a movement still in its infancy.

The Majority groups need something different from Innovators and Early Adopters. They might agree veganism is ethical in principle, but still feel uncertain, defensive, or simply not ready. In focus groups, we’ve heard many people say they will change when others around them do. The reality is: change is scary for most people, especially when it’s entangled with identity and tradition. Most people want to fit in with their in-group rather than go against the tide, and will only change when it feels safe to do so.

3

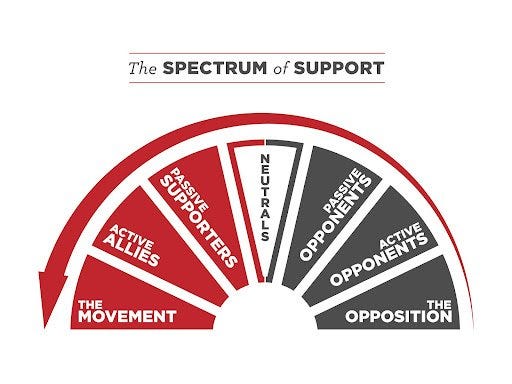

The Spectrum of Allies shows how to reach these different groups. Developed by organiser George Lakey, this tool maps people by their current relationship to a movement, from Active Allies, to Passive Supporters, to those Neutral/conflicted, or Opposed.

It shows that movements rarely win by overpowering the ‘opposition’. They win by shifting support away from it. The goal is not ‘converting’ everyone, but moving each group one step closer.

So how do these frameworks align?

Innovators and some Early Adopters are often Active Allies: they’re more open to change, talking about it to others and even taking action. Some Early Adopters and most of the Early Majority sit among Passive Supporters: people who do not need convincing but do need an appealing invitation and normalisation. The Late Majority are often those who are Neutral/conflicted as well as some Passive Opponents, and they’ll only shift when social norms and environments do. Laggards are usually the Active Opponents, who are the least likely to change and the most vocal in their opposition.

Veganism’s position in the Overton Window maps closely onto where we are on the Innovation Adoption Curve, while the Spectrum of Allies asks: how do we invite passive allies into action and shift those who are neutral towards support?

Are we measuring the right things to understand ‘effectiveness’?

While vegan adoption may have slowed in recent years, some studies indicate meat reduction has increased by about 17%. In fact, some countries have already passed ‘peak meat’ consumption (like Canada, New Zealand, Switzerland). And even in other countries where meat consumption has been going up due to population growth, it has also been going down per capita.

In the UK, veganism has shifted from unheard of and unthinkable to mainstream and acceptable. Most restaurants now have multiple vegan options, or even entire vegan menus. While veganism is more likely to be positively referenced in media, TV and films, supported by celebrities, and is no longer the automatic butt of jokes.

For those of us who have been vegan for over a decade, the change is stark. Organisations like Veganuary have been instrumental in shifting that landscape. They offer invitations, not demands – creating community, offering practical support, and normalising what once felt radical. Veganuary frames veganism as a month-long experiment rather than a lifelong identity shift, lowering the barrier to entry while still opening the door to deeper change. It’s no overstatement to say our movement (and the wider culture) wouldn’t be where it is today without organisations like them.

So could this normalisation be creating the conditions necessary for the Early and Late Majority to eventually make the shift? If only current vegan numbers are examined, the profound cultural transformation that has been achieved – which may be essential for reaching those next waves of adoption – gets missed.

What these numbers also miss is veganism’s role in building movement culture. Vegan communities create the spaces, norms and shared identity that can turn individual concern into sustained collective action – scaffolding that is invisible to metrics but essential to any movement’s survival.

What can we learn from movements that shifted behaviour at scale?

If direct individual change messaging has limitations, what can we learn from movements that successfully shifted individual behaviour at scale? The tobacco control movement offers some helpful insights.

Within just a matter of decades, smoking went from doctor-endorsed advertisements to widespread stigma and restriction. What proved effective? The stigma focused not on individual smokers, but on the tobacco industry’s deceit.

The more recent Truth campaign brilliantly reframed choosing not to smoke as an empowered boycott of a harmful industry, aligning with young people’s identity and values, rather than reinforcing the common frame of smoking as something ‘bad’ to give up.

The campaign’s goal was to shift smoking from being seen as an individual choice to a collective burden imposed by deceptive corporations.

Yet tobacco control only offers our movement a partial blueprint. Quitting smoking does not threaten cultural identity the way changing diet does. It’s not woven into family gatherings, holiday celebrations, or how people express love and care. But it does suggest an approach worth pursuing: framing the industry as the ‘villain’ rather than individuals. When a movement centres industry accountability, it stops positioning advocates as a threat to people’s agency or ‘good person’ identity. Instead, it exposes how everyone was lied to, and refusing to buy into those lies becomes empowerment rather than sacrifice.

Individual change vs systemic change?

Individual change and systemic change are two of the key strategies our movement is focused on. Rather than working in opposition, they’re often complementary.

Individual change is effective for people further along in their journey, already asking: “What can I do?”. It changes demand, withdrawing financial support from Big Animal Ag, and creating market demand for alternatives. It can also act as a gateway into sustained activism. Many of the movement’s most committed organisers, campaigners and leaders first entered through personal change. Veganism can reshape identity, values and willingness to act, building the organiser base movements need.

Systemic change alters the context society lives in, changing supply. When advocacy pushes for plant-based defaults in institutions, a ban on factory farming advertising, or shifts in subsidies away from farming animals, it changes the environment shaping everyone’s choices. When schools serve plant-based meals, children grow up in a different food culture. Systemic change doesn’t only respond to current sentiment; it shapes the context for future generations.

Should people be offsetting meat?

Some have suggested a third path: donating to ‘offset’ meat consumption in order to reach those further back in their journey. But should the comparison to carbon offsetting give our movement pause? That strategy has largely allowed corporations to continue harmful practices while placing the onus on individuals to pay, without building public pressure for systemic change.

Yes, offsetting could fund important work and attract people who might not otherwise engage. If framed carefully – as a starting point rather than an endpoint, and paired with education about industry harm and pathways to deeper action – it might reach audiences further back in their journey who aren’t yet ready for diet change.

But important questions should be considered. A key one: would we ever suggest offsetting harm if the victims were human? Offsetting only works as a concept when people accept that the harm can continue. And yes, most of society does already accept this – which is exactly why adopting offsetting as a strategy risks cementing the very belief we need to shift. It could reinforce the most entrenched narrative our movement is up against: that farming and killing animals is acceptable as long as they’re treated ‘well’. This is precisely the narrative that allows welfare-washing to flourish and factory farming to continue.

It also risks treating the problem as one of mathematics rather than justice – as if freedom and life are something to be traded rather than rights that should be protected. Perhaps we need to ask: is offsetting a capitalist solution to a problem capitalism created – one that commodifies animal lives while leaving the fundamental exploitation intact? And how does it shape what kind of relationship our movement builds with the public, how we frame both the problem and solution, and ultimately what vision we’re communicating?

When the public-facing story becomes “keep eating meat, just pay to cancel it out”, industry responsibility is obscured and other animals’ desire for freedom is erased. The question shifts from how we stop harm to how we can comfortably live with it.

Cultural shifts that lead to lasting social change tend to come from expanding the circle of people who see themselves as part of the story in a meaningful way. A movement built mainly on transactions rather than participation may raise funds, but it is less likely to generate the shared identity and sustained pressure needed to transform culture and confront entrenched industries.

Individual change strategies have not yet built the movement power needed, as we’re still in the Early Adoption phase. But at Project Phoenix, we don’t believe the solution is replacing them with financial transactions that risk normalising the very system we’re trying to dismantle. We believe the solution is building a movement ecosystem where personal change, systemic advocacy and strategic funding work together by telling a more powerful story – one that centres animal freedom.

Veganism remains a powerful and necessary ask. It represents living in a way that causes the least harm possible. Offsetting could raise needed funds and reach new audiences, but only if strategically framed as a bridge towards deeper change and action, not as an endpoint. Without that framing and without keeping animal freedom as our north star, we risk losing the heart, soul and moral clarity that makes our movement what it is.

Do we need a portfolio of strategies?

Successful movements do not rely on a single theory of change. They operate as ecosystems, using multiple approaches at once.

Personal transformation can build a base of committed allies. Mass protest and community organising can generate momentum and public attention. Inside-game tactics can translate pressure into policy and institutional change. Creating alternatives can demonstrate what is possible. And structure organising can build the leadership and infrastructure that sustains everything else. These approaches are interdependent – movements need all of them.

At Project Phoenix, we believe our movement should continue inviting people to embrace, or at least try, veganism, while recognising this ask is most effective for those further ahead in their journey and already contemplating change. For different people, veganism may need to be framed differently: such as a collective action rather than an individual one, an aspirational identity, or a refusal to support violence. We may even need to avoid the word ‘vegan’ for some audiences.

For broader audiences, centring industry accountability might be more effective. This shifts attention away from any sense of individual moral judgement and towards the systems directly causing harm, without absolving anyone of responsibility.

Alongside this, sharing journey stories and highlighting social proof helps people see that change is possible, it’s already happening, and it can benefit all of us.

Meeting people where they are – whether it’s through reduction, incremental reforms, single issue campaigns they already care about, or other meaningful entry points – can create pathways into deeper engagement and may reduce recidivism by allowing people to move forward at their own pace without triggering resistance.

This is not about diluting our message. It’s about matching our asks to audience readiness, values and identities – and building an ecosystem that can turn concern into sustained action and pressure.

We are playing the long game

The modern animal freedom movement is still in its infancy. Social change takes time, and while it never feels swift enough, that doesn’t mean particular tactics should be abandoned (unless they cause harm).

Does the slowing in vegan numbers mean individual change is ineffective? Or does it mean the movement has reached most of those predisposed to innovation and early adoption, and the next phase requires different messages, different strategies and persistence?

Encouraging signs are everywhere: meat reduction is increasing, cultural acceptance of veganism is growing, infrastructure is expanding. The context is shifting in favour of animal freedom, and organisations like Veganuary and The Vegan Society have been instrumental in making that happen.

At Project Phoenix, we believe the movement doesn’t need to choose between individual change, systemic change or strategic funding. It needs all of it: a portfolio of strategies grounded in research that recognises different audiences need different approaches. It needs a movement ecosystem that can meet people across their entire journey – from first questions to lifelong commitment. And it needs a recognition that social change is messy, non-linear, and requires diverse tactics working together, rather than undermining each other.

A slowing in vegan adoption is not a sign of failure; it’s an invitation to evolve. How our movement responds now will determine whether veganism stalls or breaks through to achieve the mainstream adoption needed for animal freedom.

We’d love to hear your thoughts on this issue. Leave a comment or send us a message. Let’s keep this conversation going…

Thank you. A really thoughtful analysis. Veganism has to be the moral baseline of our movement.

I agree with the statement at the end: "The movement does not need to choose between individual change, systemic change or donations. It needs all of it: a portfolio of strategies grounded in research that recognises different audiences need different approaches."

As someone who focuses more on systemic change, I think the movement has reached a point where we have an imbalance, with too much focus on individual change and not enough focus on systemic change to support individual change and make personal transitions easier.

On a different note, perhaps the donation ask could be reframed as, "Going vegan would be great, but if that seems too difficult for you right now, you can start helping by simply donating".